Interview w/ Arturo Kameya

Irene de Craen: You’re interested in the life of museum objects. Can you explain what you mean by that?

Arturo Kameya: ‘Museums of ethnography keep a great deal of things that together we refer to as ‘material culture’. I am fascinated by the way we put a lot of effort into saving and restoring, and how we are able to give multiple dimensions to a limited quantity of objects. Before they entered the museum these objects were used for other purposes like ceremonies and everyday life activities, but we stripped them of their spiritual and everyday use value. We keep them and then focus on the matter which is left.’

‘During my research for the exhibition Ghosts don’t care if you believe in them at Hotel Maria Kapel I spoke with a conservator of the Tropenmuseum. He told me that past methods of exhibiting objects are now considered incorrect. For example when they tried to make a theatrical resemblance to the place of origin. Now their view has changed and they try to be as respectful as they can be. Meaning there is a limitation on how much conservation they’ll do. So sometimes they won’t restore something, even when it’s crumbling or broken. This new method is dictated by a new philosophy and the understanding that there are some things that shouldn’t be touched or replaced because they belong to another culture that we must respect. This makes me wonder about the objects themselves. The meaning of objects is constantly changed throughout the history of exhibition making, even though the material part stays the same. How must they feel?’

IdC: How must the objects feel?

AK: ‘Yes. What do they think? If you would be one of these objects and you’re displaced, how would you deal with it? There’s such a great quantity of politics between the place of origin and the place of exhibition. Most of these objects have gone through a trail of violence. When you’re looking at an object in a museum, you’re not just looking at the objects, you’re also looking at the routes they took and the history of how they got to the museum. I call this the material afterlife, or the anthropological afterlife of the object. Museums are struggling to deal with the spiritual meanings these objects used to have, and how to represent that without being disrespectful. But how can you show the spiritual value of an object when you only focus on the material aspects? You end up erasing so many aspects of the object, so many things it represents. To me this is very difficult, to the point where I wonder why we even have these kinds of museums at all. Sure, it’s important to have them for future generations and as a way to understand the past. But to me, there are more important ethical questions that arise, and it’s going to be more difficult to sustain the existing discourse over time.’

IdC: The works in the exhibition have a lot of references that you use to discuss the things you’re talking about here. One of these is the painting The Funerals of Atahualpa by Luis Montero, completed in 1867. Can you say something about why this painting is important to you?

AK: ‘I was thinking about the mobility aspect of objects and I wanted to have a starting point to work from. I decided to focus on this painting because it intersects with a lot of issues related to objects in museums. For example, the painting was made by a Peruvian painter in Italy in the nineteenth century. He had a scholarship there and he started to paint the funeral ceremony of the last Inca who was murdered by Spanish conquerors. The work represents the first Peruvian painting of its kind that shows someone who is not white; the main character, Atahualpa, actually resembles a native person from the Andes. That was quite a game changer in the nineteenth century and in the history of painting in Peru. On the other hand however, all the Inca women that appear in the painting and are trying to interrupt the funeral ceremony in order to take the body to a more proper Inca ceremony, are all women with European features. Their clothing is a mix between Andean and European style clothing.’

‘It is said that the figure of Atahualpa is actually modelled after a deceased Peruvian friend of the painter who was also in Italy with a scholarship. So many things get mixed up in this one work. I think this is a very interesting cycle. Luis Montero was trying to reflect on his postcolonial identity, but he ended up treating real people like objects. Then when the painting was finished and he couldn’t get it into the Salon in Paris, the painting travelled through South America, via Rio de Janeiro, Buenos Aires, Montevideo, to Lima in Peru where it is till this day. He didn’t sell the painting, even though there were many offers, because he wanted the painting to be in Peru and represent a kind of national pride.’

IdC: So how does the painting figure in the exhibition at HMK?

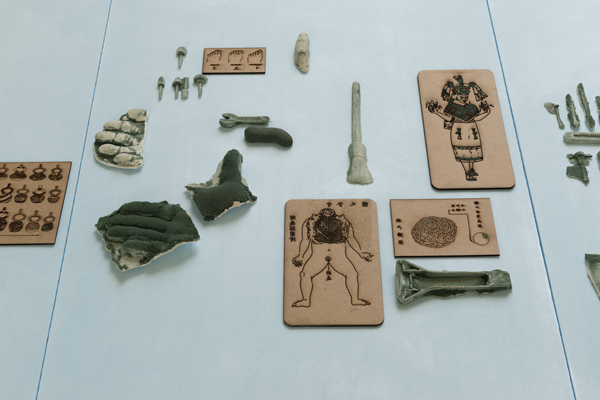

AK: ‘There’s a piece in the exhibition, a mountain made of plaster and foam. On this mountain and around it are small sculptures and objects that refer to the painting, especially from the centre part of the painting where Atahualpa is lying. Even here, he has a chain around his wrist. There is no life in his body, he is a dead man, but he is still chained. In a way this reminds me of the objects in museums and how, no matter what, they’re still bound to certain mentalities that constrain them. They are not free and they’re never going to be free.’

IdC: You’re also referencing methods of forensic reconstruction. Can you say something about why and how this is related to ethnographic museums?

AK: ‘I find it interesting how techniques of facial reconstruction are used on people from the past. For example, there’s one very famous case of human remains from the pre-Colombian times of Peru: El Señor de Sipán, or the lord of Sipán. The forensic processes and methodologies the researchers use make the old grave look like a murder scene. This is because they use the same methods they use when investigating a modern day crime. It is interesting how these worlds cross, and you start to think about how it’s kind of the same in some aspects. It aims to recreate a history of violence. It makes sense of course that the same techniques are used, but it also gives me an uneasy feeling about how we treat the objects and how we put importance on technology to recreate the past and see ‘how it really was’.’

IdC: The exhibition text states that one of the aims of your research is to question what cultural cannibalism means today. What do you think it means?

AK: ‘The materials I used for this exhibition are all materials that are usually used for restoration purposes and for making replicas. I was thinking how the life of objects becomes like a cycle of simulations. It’s like the ship paradox: when you restore a ship over time, replacing the broken pieces, at some point the entire ship has been replaced. Then, is it still the same ship or not? To me, cultural cannibalism is like that. You eat or devour parts of the original until you’ve changed it completely.’

IdC: Isn’t that the point of cultural cannibalism?

AK: ‘Yes, but you end up with some questions that are very difficult to answer. What is actually the thing you’re looking at? I find it interesting that you’re always constructing and destroying. To me this is a metabolic or organic cycle. It is a never ending cycle of eating the other, of having this primal urge or need to devour the other.’

IdC: You refer to museum objects as ‘ghosts’. Why this term?

AK: ‘The term refers to the spiritual world of things you cannot touch or see. Whether you believe in them or not, ghosts have been around throughout the history of humanity. Every culture has a form of spiritual belief in the afterlife and what happens to your soul when you die. The term ‘ghost’ then, works in two ways. The first is on a spiritual level when thinking about the life of objects. What if they were really alive and conscious of what they’ve been put through? How would they behave, what do they think about being immortal in this limbo of the ever-changing world they live in? And on the other hand, although material culture is that which we can see, the history of the object – from when it was found to the moment we are looking at it – is like a ghost. The object is like a sponge. You can see the imprint of how all these politics have worked on it throughout time. And now they are stuck, literally in bondage in museum storage, wrapped with foam and belts etc. Somehow it’s all connected.’

Originally published in Studio Note #7 (April 2018), Hotel Maria Kapel (HMK) (SN7online.pdf)