Feather Hat Variations

With the piece Feather Hat Variations artist collective Mahony analyses the possible conflicts that arise when a story becomes history. The artists refer to the unsolved question of how “El penacho de Moctezuma”, the feather headdress of the Aztec Emperor Moctezuma II, ended up in the Museum of Ethnology in Vienna and follow discussions on whether the headdress should be given back to Mexican authorities. In 2011 Mahony decided to bring a Tyrolean feather hat to an exhibition in Mexico and therefore add an additional layer to the story. Turning the hat itself into a symbol for an unsolved storyline, the work has been shown in different versions since then.

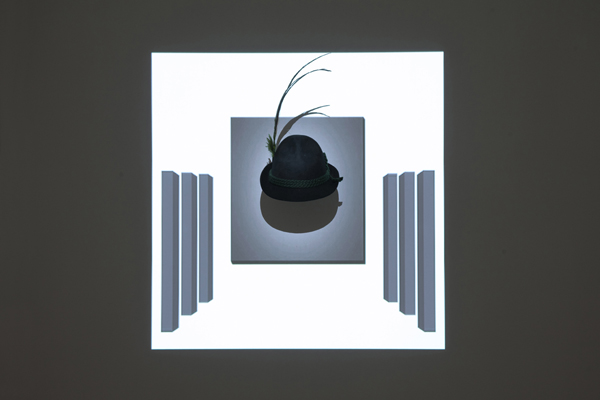

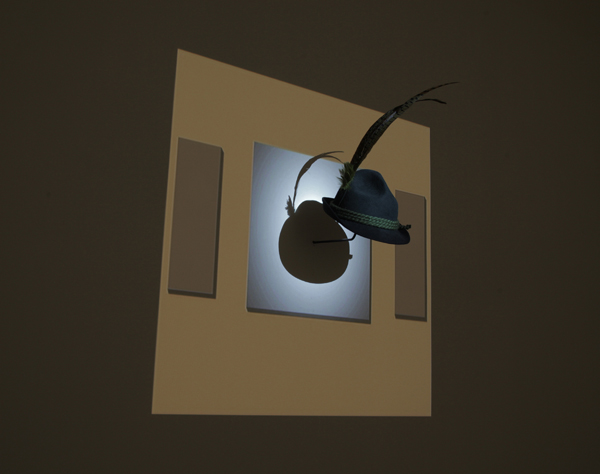

For the installation Feather Hat Variations Mahony projects abstract sketches of display arrangements onto the Tyrolean hat on a wall. The additional audio for this installation is a read version of text samples, taken from the original text that was accompanying the display of the penacho in the “Museum für Völkerkunde Wien” (Museum of Ethnology Vienna) in 1992. In 2013 the museum was renamed as Weltmuseum Wien. It was closed for renovation since 2014 and reopened in 2017, with a modified way of displaying the penacho.

The history of the Viennese feather headdress can be traced back to 1575 when it was identified together with other feather items in the inventory of the Kunstkammer Count Ulrich von Monffort in Tettnang (Upper Swabia) as “sundry Moorish feather armature.” Its appearance in the provincial collection of Count von Monffort illustrates the further spread of such works in sixteenth-century European collections. The Tettnanger Kunstkammer was purchased by Archduke Ferdinand of Tyrol in 1590 and became part of his Ambras collection, which was moved to Vienna in the nineteenth century. In 1880, through an exchange from Habsburg family property, the headdress was acquired by the anthropological-ethnographic department of the Natural History Museum, predecessor to today’s Museum of Ethnology in 1928. The piece did not arrive in Austria from Spain through Habsburg family relations.

Through Spanish conquest, Mexico, the “new Golden land” became visible on the European horizon. Aztec and Mixtec works of gold, feathers, and turquoise were marveled at as examples of foreignness and were preserved in the wonder chambers of European sovereigns and scholars. After the first intoxication of novelty subsided, the remains themselves of a destroyed world fell victim to vermin and neglect. Fewer than one hundred of these objects (many of early colonial origin) have been preserved until today.

The treasures found in Vienna, which include three of the six surviving feather works, are from the sixteenth-century Habsburg collection, but cannot be traced back to family relations to the Spanish Habsburgs.

“Headdress made of quetzal, cotinga, cuckoo, Eurasian spoonbill feathers, and gold discs”. The feathers are woven to a plume and reinforced with rods. Until the eighteenth century, there was a gold bird’s head in the middle of the forehead (perhaps on a face mask), lending the crown a bird-like shape.

In Aztec Mexico, especially valuable feather jewelry was among the ceremonial attire worn by priests when performing rituals. The only preserved feather headdress from pre-Spanish Mexico belonged to such a costume. Due to a lack of knowledge in the nineteenth century, the piece erroneously became known as the “feather crown of Montezuma” whereas, like all Aztec rulers, Montezuma wore a turquois diadem as a sign of his grandeur. The feather piece was acquired in 1590 by Archduke Ferdinand from Tyrol as part of the Tettnang Kunstkammer of Count Ulrich von Montfort. There is documentation of the headdress as part of the collection in an inventory listing from 1575. A golden bird decorating the forehead was lost in the eighteenth century, as well as the original face mask on which it was affixed.”

The old Mexican feather headdress in the Museum of Ethnology cannot be the feather crown of Montezuma, because such a crown never existed. Montezuma was an Aztec ruler and as such, wore a turquois diadem, like his predecessor, as a sign of his position. The feather headdress was also not among the so-called “offerings of Montezuma” that he brought to the Spanish conqueror Cortez in 1519.

Feather headdresses, like the one held in Vienna, were part of the ceremonial dress worn by Aztec priests in connection with rituals. The only surviving example from the one hundred similar objects once in existence, of which a dozen arrived in Europe in the sixteenth century, is the one in Vienna, owing to its careful preservation. One reason for its identification as an Aztec imperial crown in the nineteenth century was its apparent uniqueness, which has meanwhile been recognized as an error.