A conversation about ‘Notes from a trembling community…’

Irene de Craen (IdC): We started this project from the ideas of poet and philosopher Édouard Glissant (1928-2011) and in particular his concept of Relation. This is a key concept in his thinking, but probably also one of the most complex ones. With it he proposes a way of relating to each other, and everything around us, that is not based on a binary, not based on seeing the Self only in relation to the Other. This kind of binary thinking is common in Western philosophy and is arguably at the root of many problems we face today such as issues around borders and walls, the free movement of people, refugees, as well as nations and people withdrawing into themselves because they believe in a false notion of identity or tradition as something that can be threatened or damaged by the Other. Glissant therefore sees his concept of Relation as the key to transforming mentalities and reshaping societies. However, by his own admission Relation cannot really be defined, but only imagined. So how are we supposed to talk about it?

Season Butler (SB): I think we dealt with this by approaching the whole project as being in a constant state of becoming. We didn’t have an idea and then seek to realise it. It has been constantly unfolding, which is exciting because we are both participants and observers.

Jenny Wolka (JW): Exactly. I think for us it is very clear that this was also the first chapter in experimenting with a new type of collectivity that we started to develop during our Commonplace meetings in Berlin over the summer of 2018. This is a process that takes a lot of time, so in a way what is observable in the exhibition is a studio situation, that somehow got translated to a public space.

Clemens Leuschner (CL): For me many of our processes and discussions come together in the show quite clearly though. I think for instance about how Aiko’s sushi workshop during Commonplace in Berlin questioned the notion of tradition or the status quo of a working system. This is not only related to her own work but also to some of the other works in the show, for instance the Transkutir text which you can read while listening to Leo’s soundtrack. His sound piece makes me think about one of his lectures during Commonplace on Afro Rhythmic Mutations in the Americas. In my mind I hear Judith reading the Cosmic Manifesto out loud while being interrupted by the staccato sound of Season’s typewriter. With every sentence the balloon rises a bit higher. She tries hard to follow the words, but cannot grasp all of them; something gets lost in the space of the invisible, poetic and violent borders of translation. The images of the baskets by Coletivo Kókir fluctuate between ‘useful’ objects and ‘just’ artworks, as I come through the leaves of Luz’s Poetic Borders to the ‘end’ of the world. While listening to some sad British tourist being afraid of robbers stealing the end of her land, of the nation she loves, I think about European borders, where nobody gets in anymore, nothing gets out. It´s like the science fiction script Esper talked about during Commonplace – and I find myself standing next to the wall in front of a poster by him and Maurits, which depicts a sad ‘raising star’ of Europe. And this is just one walk through the show, not even describing all of the works…

JW: Which brings us to another question; a question that is inherent to any contemplation about conceiving a show, as a presentation of something to a possible audience. How do you translate thoughts and sensations into dialogues between the pieces in the show, and finally how do you communicate this to someone else? Maybe that is why we decided to install a collage of audio recordings in the entrance of HMK, so that by walking up the staircase the visitors could listen to our different voices before even entering the show. The collage consists of cut-out phrases from the discussions we had during Commonplace, when we started to invite fellow artists and thinkers to join our ongoing talks, and which is really the basis of the whole project. This audio-collage reflects somehow on the underlying desire for creating something new out of the transmission of ideas.

Judith Lavagna (JL): Yes, because we also opted for the title Notes from a trembling community in a willful state of flux to show that the whole project reflects on the processes of a collaborative research which is still ongoing but paradoxically finds its form in an exhibition. We were very conscious about the limits or fragilities of translating this research, and so we tried to find a form of display that reflects on its own making. Furthermore we aimed to break with some exhibition standards, for example by using the concept of the archipelago as a way to let works overlap and interact, which was particularly challenging because of the multiple languages and materials used. The experience of making this exhibition kept us open to the friction the different works in the exhibition could bring. New works were produced or commissioned but we also brought existing artworks, texts, and sound pieces. At the risk of ‘freezing’ the discussion by exhibiting, we looked for a way to keep a conversation going.

JW: But all of this has only been an entry to the readings of Glissant which we now have to explore deeper because we are really just touching the surface. For example, there is this poetic approach in the exhibition at Hotel Maria Kapel, but there’s also always a political approach with Glissant. The danger might be to approach Glissant on this poetic level and forget where he’s really coming from. How are the very complex ideas of Glissant translated into this show? Because maybe there is a breach between Glissant’s very anti-colonial context and some of the poetic thoughts. This space in between I find very interesting and that should be developed further.

IdC: We’ve also really tried to embrace the idea of opacity, another key concept of Glissant’s thinking. Simply put, opacity is the opposite of transparency. Glissant thinks we should embrace the untranslatable and unknowable and sees this opacity as a way to challenge and subvert systems of power. He demands a ‘right to opacity’ and calls for an understanding and accepting of difference without measuring this difference to an ‘ideal scale’, comparing it or making judgments. For me it has been a personal struggle to put this into practice because of how I’ve been conditioned to approach critical thought and exhibition making.

JW: Of course, but it can also be easy to hide in this idea of opacity. In Glissant’s sense I find it very appealing, but in the context of art it is sometimes used as an easy way out.

SB: I really agree with that. Glissant’s idea of opacity was grounded in our [people of colour’s] right not to explain ourselves, not to have to give account of ourselves. That’s the only way I can really reconcile what Glissant says about borders, which is one of my sticking points with his philosophy. I think the idea of poetic, permeable borders is quite naive because borders are the site of violence, borders are the lines that are drawn when you are Othered, and the ability to permeate borders is exactly social privilege. And so being able to have opacity and not have to explain why you want to cross a border but just being able to cross, that’s our privilege in some ways. But then also I think we were trying to unpick something opaque and find out how it worked in Oliver’s performance score, for example. That was a moment of testing the relevance of opacity, where it applies and where it’s not useful.

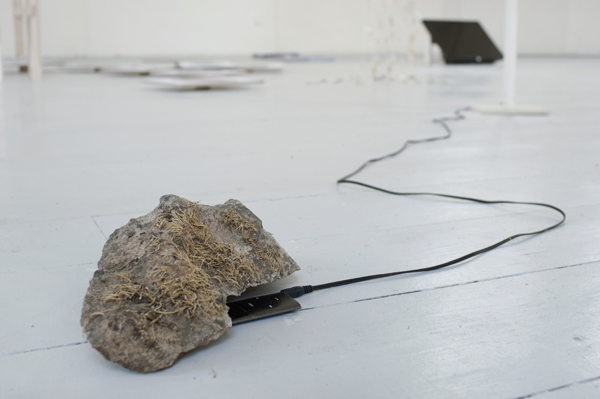

IdC: I also find it difficult to understand what Glissant’s point is with borders. He says borders should not be dissolved, but that our mindset about them should change. It is a very idealistic way of seeing a border not as a instrument of control and power – which it is – but as a way to maintain difference, or ‘different flavours’ as I believe he says in the film One World in Relation by Manthia Diawara which we screened a few days before the opening. But our way of thinking about borders, geography, and nation states is so much tied to privilege as you say Season, and with that power and control, that I don’t believe it is something we can easily overcome. That’s why I find the Land’s End work in the show so enticing while thinking about these things. Mahony took the most western part of England and people are so uncomfortable with that, even afraid that something is being taken from them… while of course it is just a rock that has no inherent meaning besides the one we give it. In that sense the opacity that is intrinsic in art really works to deal with these complex issues.

Originally published in Studio Note #9 (December2018), Hotel Maria Kapel (HMK) (download here)

Image: Mahony & Gerald Mandl, Land’s End, stone and sound piece 6’3”, 2018