The Invisible Borders

Ania Molenda in conversation with Merve Bedir on the possibility of “living all together” despite borders.

Ania Molenda: Where did your interest in working with the notion of borders and migration come from?

Merve Bedir: ‘About three years ago I was studying the spatial aspects of the “arrival neighbourhoods” in Istanbul. Some of these neighbourhoods are places where the Kurdish people, displaced from cities in southeast Turkey, and other migrants from Russia, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Turkmenistan or African countries, have settled especially over the last 20 years. After the revolution in Syria in 2011, I began researching how the migration that resulted manifests itself in cities and at the border between Syria and Turkey, as well as in other countries like Bulgaria and Jordan. Borders are necessarily tied to a history of conflict and migration. In this sense, this is not a new story. In 2014, I curated an exhibition entitled “Vocabulary of Hospitality,” which was an annex to Volume’s travelling “Architecture of Peace” exhibition (1). This exhibition is when my work first became visible.’

AM: Often when we talk about architects’ involvement in the issues of war and migration, we think of the provision of shelter. Your focus is more on the social aspects of integration. Has it always been that way?

MB: ‘The reason why I haven’t been looking at the issue of shelter is that it was heavily politicized in Turkey through refugee camps. I didn’t really want to be instrumentalized by these politics, where you cannot even question the notion of “public” in a camp. Instead, I prefer to ask “How can we live all together?” To me, stating the question this way separates it from nationality and politics, and also from questions of the temporary and permanent. When I look at shelter, I want to analyze it as a concept and understand how it works. It does not concern only refugee camps. Reception centres and detention centres are also forms of shelter for refugees. I see shelter as part of a bigger narrative of how we live together. At the same time I am well aware that the provision of shelter is urgent. It is the first and foremost need that we react to in a state of emergency, and mass migration is a state of emergency. However, I don’t think we can look at it only through that lens.’

AM: Legal structures that could resolve the emergency and resume “normality” are so complex that the slowness of implementing these laws often put migrants in a situation of a permanent transit. You just mentioned that we cannot look at the issue of migration only as an emergency; what’s your point of view on the issue of temporality in addressing problems of migration?

MB: ‘That’s in fact one of my biggest worries when I hear about building refugee camps or hosting refugees in general. The emergency resulting from mass migration is different than the one of a natural disaster, because it is a part of international affairs, national borders, citizenship, security, sovereignty, war and politics. This permanent temporariness, you mentioned, in many cases comes a result of how the state of emergency is used as an excuse to suspend the law. We can see it in the recent example of Denmark confiscating refugees’ belongings, and Germany, Hungary and France have also acted in similar ways. By suspending the law, the state creates for itself a space to act; but in a situation where the law is suspended and people try to sustain their lives, permanent temporariness pushes them into a limbo. To become permanently temporary means that there is nothing to hold onto, you don’t know what is to come, you don’t have any prospect of the future, and where there is no law, anything can happen.’

‘Another reason why refugee camps are permanently temporary is the status of the migrant, the length of the asylum process and the duration of the conflict itself. In the Netherlands, an asylum seeker has to wait a year to obtain a refugee status. In Turkey, before 9/11 it was around six months and now it is more than six years. In some African countries the average time spent in a refugee camp is thirteen years. So this is what a permanently temporary situation is like, but it is more than that, it is being in an ambiguous situation where you don’t know what the future is. Basically, the future is full of terror.’

AM: When we look at the way refugee camps are built, they are implicitly meant for a temporary stay. In reality they are occupied for periods of time that are difficult to classify as temporary: thirteen years sounds permanent to me.

MB: ‘There is a lot of discussion about refugee camps. One of the most recent ones is that IKEA is designing units for refugees and selling them to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). The cost of providing a UNHCR tent for 13 years is around 169 euro. The IKEA unit costs ten times more. It is a significant difference to what UNHCR can or should provide. I am sure that IKEA’s unit is much more comfortable, but is it what we should focus on? Should we focus on making the tent more comfortable or should we focus on finding a way to stop the war that forces people into the situation of refuge? I cannot understand how such an economy can be constructed around it.’

AM: I agree that this is very difficult to understand, but it seems that the problem of war and borders is not just a physical one. Borders between nation states in general become more abstract and transform into internalized boundaries within cities and societies. I find the investigation on the language you made for the “Vocabulary of Hospitality” exhibition really interesting. Could you tell us a bit more about how this work started?

MB: ‘When the migration caused by the war in Syria started, the politicians in Turkey referred to Syrian refugees as “guests”. This word sounded great on television, but when the refugees arrived, they faced all sorts of problems related to health and shelter, and later on in education and work. They didn’t speak the language, so the reality had nothing to do with them being our guests. The fascination and horror for the context in which this term was used inspired me to look deeper into the layers of language and ways of reading them through urban space. Through an analysis of the language in Derrida’s “Of Hospitality” I curated the exhibition “Vocabulary of Hospitality” that read into various meanings of the word “guest”, such as ghost, host, or hostage in different spaces in Istanbul and other places in Turkey. One of the aspects of spaces of migration in the city is that while borders are getting more porous and/or obsolete internationally, they reappear in an invisible way within the city.’

AM: In “Vocabulary of Hospitality,” you also mention that the refugees are sometimes not perceived as guests, but as parasites. Paradoxically they were seen that way, because they didn’t work (i.e. didn’t contribute to economy) but in fact they were not allowed to work. This perception is rooted in how most people understand very little about the situation of refugees and don’t know what the legal limitations are.

MB: ‘This is such an important point. Maybe we should not expect people to know everything about asylum, refuge and the highly hierarchical legal issues around them. If we look into the actual definitions, a refugee is someone who has a permanent residence permit in a country, an asylum seeker is someone who applied for the refugee status, a migrant is someone who left their home country and a stateless person is someone without a passport. We do not need to know these definitions except where they intersect with reality. In Turkey, for instance, asylum seekers are not allowed to work, yet they do work, so in the public eye they take others’ jobs and create competition. That often leads or adds up to issues of racism, xenophobia and hatred. This makes me think that what we should expect should actually be from our governments in terms of human rights, equality, the freedom of movement, and so on.’

AM: Do you think that the withdrawal of governmental engagement from bringing actual solutions and clarity to these issues results from a lack of interest, or an actual crisis of the nation state as such?

MB: ‘Let me answer with an example. Recently both Mexican and Sicilian drug dealing bosses sent messages to ISIS to warn them “not to mess with their networks” after ISIS attempted to block the drug networks in their territory and the vicinity. Both mafia networks have huge influences there. So we see a situation where a terrorist organization declares itself a state and drug dealers exchange warning messages with them. To me this shows an enormous crisis of the nation state and the obsoleteness of the national borders.’

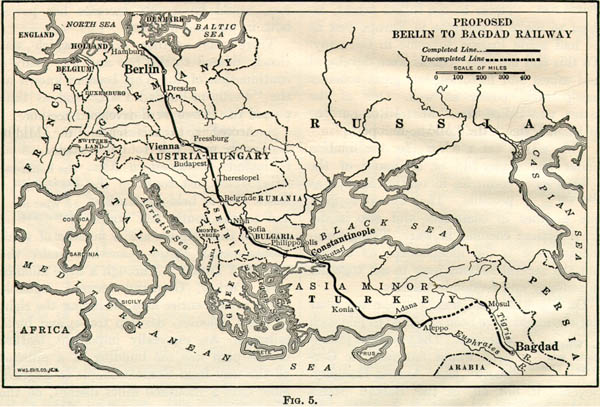

‘For me, the very idea of drawing a border based on a train line, for example, which is how the border between Syria, Iraq and Turkey was drawn, separating villages and cities into different nation states, puts national borders into question from the outset. It is natural that after the war broke out all of the inhabitants migrated and the border was practically cancelled. Borders that were not drawn by the people of the region, such as those in Turkey, or between many countries in Africa, are not functioning. People find and will find every reason to break the rules and redefine them.’

AM: Is there something we can do to respond to that crisis?

MB: ‘I think we need to act more locally, because on a smaller scale we’re more able to make decisions about our lives and negotiate them with others. Not only the issues we might have with refugees, immigrants and migrants, but also other things, like the heights of the buildings, the location of schools, who will attend them, how much green space there will be – all of these things.’

AM: All of these decisions are politics, but the word politics nowadays is associated more with a political system than with the actual politics. At the same time these two definitions seem to grow further apart, because what is happening on the political arena often does not respond to the needs of the citizens.

MB: ‘I’ll give another example. There is a word in Turkish called “hemşehri” that means “people from the same city,” and I would like to think of citizenship on that scale as well. We are much more attached to people from the same city or neighbourhood with us because we share the same issues that are about our city, and when I say share I don’t mean that we necessarily agree and look for consensus. We confront, we look at each other from the other’s eye, and we accept each other.’

‘Land+Civilization Compositions is currently working on building a kitchen garden at the Syrian border with women from Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and the former Soviet countries. They all say that they are all from Antep, the city where we are working. They have different nationalities, but they feel that they belong to their city.’

AM: There are these two opposite movements – on the one hand we can observe that people return to their local connections that might be cross-national, but on the other hand it is hard not to see the growing wave of reviving nationalism.

MB: ‘Many people hang onto created identities hoping that they will keep them together, but I don’t know how long this way of thinking will survive. I see nationality as an anxiety common to every man and woman. The moment we forefront this notion we create a hierarchy – we declare who is the host and who is the guest. And that’s the thing with hospitality, the guests should know their position, they should know where they should sit and shouldn’t ask for more than what they have been offered. That’s why asking “how do we live all together” becomes important, because it does not imply any hierarchy.’

AM: You said that commoning can be a way of questioning the nature of borders, do you think we can we imagine a world without borders? What are ways of living all together we can imagine in a borderless reality? (2)

MB: ‘I would like to think of a borderless ideal, but people are entitled to their borders. Maybe we can at least think of open borders (for all). Some people say that we need a revolution to reach another form of living together, not necessarily based on the idea of a nation, and I’d rather say we need utopias. Currently we don’t know what we are longing for. We need to be able to think of (collective) futures and we should be able to find them, but it will not happen overnight. It will come through the struggles and problems we share.’

‘Commons reach beyond the understanding of the state, the public, the private, and the individual, they are much more collective and much more utopian, but not utopian as something that is highly idealized and/or can’t be achieved. Utopian, which we think of and practice everyday, and through which we will be able to go beyond the world that was defined by the rules of the former generations.’

By Merve Bedir and Ania Molenda, editor.

This article was first published on The Site Magazine on June 22, 2016. Republished here with permission of the author. Cover image: Aftermath of migration, Merve Bedir, Lesvos, Greece, 2016.

End notes

(1) Volume is an independent quarterly magazine that sets the agenda for architecture and design. (http://volumeproject.org). One of its long-term ongoing research projects, “Architecture of Peace” is conducted by a network of architects, urban planners and scholars on the international platform ‘Archis Interventions’ and has been featured in Volume #26 and #40. In 2014, The Good Cause: Architecture of Peace travelling exhibition presented a selection of results from this research. The exhibition was shown around the world, including Canada, Germany, the Netherlands, Rwanda and Turkey.

(2) Commoning is a verb to describe the social practices used by commoners in the course of managing shared resources and reclaiming the commons. It has been popularised by historian Peter Linebaugh and his book “The Magna Carta Manifesto” published in 2009. (http://p2pfoundation.net/Commoning)